A stock photo client calls you with an assignment. The photo buyer likes your photography and enjoys working with you and now wants you to shoot a project.

Commercial clients who purchase your stock images are likely to assume you shoot assignments. If, up to now, you’ve only shot for stock, consider this article a primer to prepare you for taking the step into assignment photography.

Unlike shooting stock, assignments are not speculative and have specific client requirements. Often these requirements are unavailable in a stock photo. For example, the client may want a photo of its product-with the logo prominent in the image-being used on a backpacking trip.

Assignments require planning, estimating/budgeting and production. Most often you are required to prepare an estimate for the client that will pull all of the elements together.

What’s the assignment?

Assignments vary widely depending on the client and the specifics of the project. You could be asked to do a simple assignment, such as photographing a biologist doing groundbreaking work in the field for a magazine article, or an advertising campaign for the latest in golf clubs that involves shooting on location at major clubs across the country for multiple promotion and advertising uses. The former requires very little production, but the latter would need extensive planning.

Your first step is to determine exactly what the client needs from you. Question what the photo shoot entails, where the assignment will take place, how many photos are needed, how the pictures will be used, and what items need to be included in your estimate. Often the client will spell these things out without prompting; but if not, be prepared to ask. And be sure the client differentiates between what is optional and what is necessary to give you both some flexibility.

Project requirements may include such things as travel time and expenses, pre- and post-production time, location scouting, photographer’s assistant(s), models, props, hotels, meals, rental car, gas and tolls, image processing, permits and clearances. Each expense is important to estimate, so gather as much information from the client as you can up front. In your estimate, keep your fees separate from your expenses.

Usage

Just because you are being hired on assignment does not mean you have to give up all rights to your photographs. Unless otherwise agreed on, the photographer owns the copyright to the images he or she creates. Your estimate should have a section that describes the usage you have negotiated with the client: how and where the client plans to use the images and how long the images will be used. Also, secure a (discounted) price to allow the client to purchase rights in the future if they so choose. If you prefer, you can spell out usage in a separate licensing agreement.

While some assignments will prohibit the photographers use of the images taken on the assignment, others allow the right to license their use. Just about anything that can be negotiated can be applicable here from no right to license images as stock to limited availability as stock images and to no restrictions at all. I have negotiated all three. While working for a global corporation that sent me all over the place, I was not allowed to license any images for any reason and for the most part, nobody would have wanted to use images with their products in them. On another assignment I was allowed to use the assignment photos for stock, but not on the West Coast where their primary operations existed. And another assignment was shooting a product catalog of outdoor products and I was able to use all images as stock 18 months after the assignment.

Pricing

Pricing varies considerably and success here is simply a matter of negotiating.

The simplest pricing approach is when the client states the budget. This is common with magazine assignments where the editor will tell you how many photos are needed and what they can pay you to procure them. Everything is up front, simple, and the photographer can take it or leave it. Typically, magazines purchase one-time rights and some electronic rights for assignments, and they may require a short period of exclusivity after their publications come out.

Another model used by some magazines, pays the photographer a day rate plus expenses, but the number and size of images also come into play. If the rates for stock use of those same assigned images is more than the day rate, the photographer is paid the additional amount. For example, let’s say a photographer’s day rate is $350. He is hired by a magazine for a two-day shoot. The resulting image use, had the images been stock, total $1,250, so the photographer gets an additional $550 after publication.

A more commercial model bases fees on the amount of time involved; the client pays the photographer a day rate. Photographers who base their fees on a day-rate can be likened to farmers raising strawberries and accepting a flat fee for a day’s harvest no matter how many pounds are harvested. The more images the client uses, the less the photographer makes.

A better option is the fee based on value received by the client; the more images used, the more value received. And the more images the client uses the more money the photographer makes.

So just what should you charge? If the client wants you to shoot for a day, then you need to research what commercial photography day rates are for your area. Contacting local photographers and mentioning you are researching rates will often provide you with a sense of what to charge. If you plan to base your estimate on value received by the client then the most important question for them is how many pictures they need and what usage they plan for the images.

Production costs

Every assignment has out-of-pocket expenses, but sometimes expenses can include hefty production costs. Consider every possible cost. If the project is large, include a request for a 25 percent advance in your budget. Then you are using the client’s money to pay upfront costs. There may be resistance here, but good quality clients understand the challenges with large cash outlays for props and location fees. While most assignments are valuable and much needed these days you have to decide just how far out on a limb you can go when there are upfront costs.

Props, models and location scouting

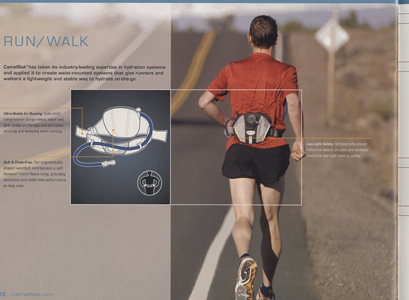

THIS ASSIGNMENT FOR CAMELBAK REQUIRED FINDING MODELS WHO WERE RUNNERS AND JUST THE RIGHT ROAD LOCATION.

Adventure and recreation assignments are common for outdoor photographers. In many cases these assignments require specific locations where the client wants you to shoot. They may require advance scouting. If so, be sure to photograph the locations that fit the client’s description so they have an opportunity to choose their preferences.

There are various ways to hire models. Modeling agencies are one option but can be costly. You can post an ad on Craigslist. Some cities have “real-people” modeling agencies where fees are more affordable than the more traditional modeling agencies. If you need models to portray athletes or outdoors people, you may be to find them where actual athletes or outdoors people can be found. For example, bike shops for mountain bikers; runners at the athletic club; and, sporting goods stores are great for campers, hikers, boaters and more. Many sporting goods store employees are eager to earn extra money themselves. So, don’t be shy; ask the salespeople at these places if they are interested in modeling for you or if there is anyone they can recommend.

Rates for non-agency models can run from nothing to trading for some of the client’s gear; rates for real models can range from $300 to $500 a day. It is crucial that models be able to perform the activity they are asked to do. Most people know how to ride a bicycle but that does not make them mountain bikers. Be sure and take a picture of each candidate to help the client decide who to use.

The client may also request props and these may need to be purchased or rented. You can find prop rental stores in your area by doing a Google search or an old-fashioned look-up in the Yellow Pages.

Finalizing the Estimate

Once you have the details from the client, it’s time to create an estimate. Let’s approach a hypothetical assignment. The client’s website sells outdoor equipment: apparel, backpacks, tents, footwear and accessories. He wants to hire you to photograph for four days in Arches National Park, capturing hiking, camping and backpacking scenes with a variety of outfits and gear, which bear the company’s brand.

Step one is to contact the national park about fees for a commercial-use permit and then obtain an insurance policy. The client will provide the props from its product line.

Next,establish hotel rates for you and your assistant and also travel costs. If you live near Moab then there may be no travel costs, but if you live elsewhere there are airfares and rental vehicles.

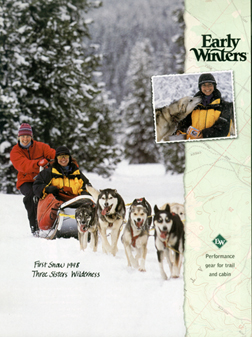

HERE I FOUND THE OWNER OF A DOG TEAM AND THE MODEL, OUTFITTED HER WITH THE CLIENTS APPAREL, AND WAS ABLE TO LICENSE THE IMAGES AS STOCK WITHIN A YEAR.

Include in your estimate the time required for scouting the park, finding models and travel time to the assignment. Your billable time for these tasks should be half of your daily rate. A qualified assistant’s fee should be about 20 percent of your fee. Include model fees, food and hotels, props and any out-of-pocket expenses with a minimum 25 percent markup. Some clients refuse to pay marked up expenses and will say so. In this case kindly request an advance payment stating that you cannot be expected to cover all advance costs. It’s fair to tell the client that you are not a bank and cannot loan them money in advance of the assignment and interest free.

To establish your photography rate, look at how many photos the client needs. Here they said 30, about 8 per day. Based on where you live and your cost of doing business, lets say $1500 per day is an average rate. Each day you will have 8 scenarios to shoot and be paid $1500 for each of those days, giving the client one image from each scenario. You will probably shoot many variations of each scenario, so state in your estimate that the client can license additional images for $200 each. Here you make more money based on how many images the client uses.

If the client ever presents a ‘work-for-hire’ contract, use caution when considering this. Here the client pays you a fee and in return you release all ownership, including copyright, to any and all images taken for the assignment. Generally, it is regarded as a bad business practice since photographers income is derived from usage of their images.

Another point to negotiate is post production of the images. If I am shooting imagery that must be Photoshopped using techniques that the client wont understand, my original estimate will state that and costs are included in my estimate. Their are plenty of other clients who have a qualified in-house design team that can process RAW files and here it is often straight photography. If they state that they will process all images and will not pay me to do it, they get the RAW files and I remind them that I am not responsible for the outcome.

Carefully consider all time and costs associated with preparing for the assignment, photographing it, and completing it. You should be paid for all time invested as well as fair compensation based on the client’s usage of your images.

Additional Info: A list of resources to help you with pricing can be found on the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP) website, at http://asmp.org/links/32 . In fact, the ASMP website offers a wealth of information on licensing, management software, legal issues, photography events and much more. Start at the home pagewww.asmp.org. A printable PDF for photo buyers (which will be helpful to photographers as well) can be found at: http://asmp.org/pdfs/assignment_photography_guide.pdf.

– Charlie Borland – BPSOP Instructor

Charlie is teaching:

Mastering Canon Flash Photography